SN69 bdo Statement on Guidelines VO 1370

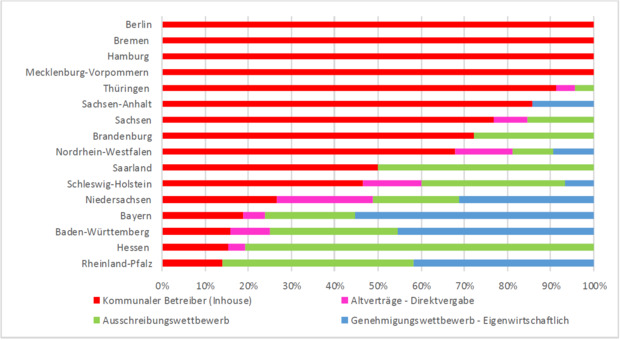

Source of the chart: bdo ÖPNV Transparency Register

Statement on the COM draft on the revised interpretative guidelines on the Regulation (EC) No 1370/2007 (Non-Paper)

The German Bus and Coach Operators Association (bdo) is the head organisation of the German bus industry and represents the interests of private and medium-sized companies in the local passenger transport, bus tourism and long-distance bus transport sectors vis-à-vis politicians and the public.

Background and stocktaking

The bdo welcomes the important initiative of the EU-Commission developed with the interpretative guideline, to counteract undesirable developments in the Member States, to create fairness and transparency and thus sustainably improve the quality of public transport.

The regulation (EC) No 1370/2007 is the result of a complex legislative process over many years, in the course of which many compromises had to be found. Just proposals on the admissibility of direct awards were negotiated by the then Federal Minister of Transport (SPD) which now make it possible for the contracting authorities to award municipal direct awards or in-house awards on a large scale, thereby excluding any form of competition for decades. competition for decades. Extreme examples here are the city states of Berlin and Hamburg, as well as eastern Germany (Mecklenburg-West Pomerania and Brandenburg), where direct awards cover the entire federal state. But in all other federal states too, the basically provided competition by Regulation (EC) No. 1370/2007 is largely excluded by direct and in-house awards. In practice, it can be seen that wherever a municipal enterprise exists, it is also provided with an in-house or direct award and thus withdrawn from the market (often for 22 years). Newly founded of municipal enterprises are also the result of this development. Private companies have been forced out of the market or turned into subcontractors. Competition has thus become the exception rather than the rule in Germany. The EU’s original approach of opening up the internal market and thus allowing state intervention only in cases of market failure has been implemented in most EU member states. Only the Federal Republic of Germany has taken a special path by relying on communal structures and thus massively restricting freedom of trade and the free play of market forces and in some federal states even completely abrogating them.

2.2.6 Article 4(7) and Article 5(2)(e) Conditions for the award of subcontracts

Although the regulation (EC) No 1370/2007 provides for a minimum self-provision quota for services, many municipal regional companies have been established in Germany which do not employ a bus driver themselves to provide regular services.

In many cases, private bus companies work as subcontractors for municipal companies that have received a direct award or provide these services in-house. Unfortunately, there is now a growing trend to reduce subcontracting to the provision of drivers. The subcontractor receives the order from the municipal company to provide the transport services, in return for which he must then rent the buses from the municipal company, have them maintained and repaired by the municipal company and also purchase electricity or fuel from the latter. In the end, the business sector is limited to the mere provision of driving personnel. The economic activity of the private companies is thus reduced to a minimum. _The bdo therefore welcomes the clarifications in 2.2.6. on the “wrong internal operator” and proposes that the Member States be obliged to regularly check and sanction possible violations of 2.2.6 by implementing “administration organisations”. _ 2.5.8 Article 1(1) and Article 6(1). Obligation to compensate public service operators ‘adequately’

A very big problem in practice is the failure to pass on the compensation funds according to § 45a PBefG to the transport companies operating their own services. The logical consequence of abandoning the discounting of tickets is unfortunately always omitted. Almost all federal states have made use of the opening clause in the PBefG and transferred the federal regulation of compensation payments according to § 45a PBefG into state regulations. Unfortunately, in all cases this transfer has led to the transport companies no longer having a direct claim to compensation for reduced revenue.

The Commission’s interpretation makes it clear that it is unacceptable to require companies operating on their own account to continue to grant the discounts (25%) to the largest user group, the pupils, without compensation. Even in cases where the districts are the biggest beneficiaries of these discounts, they refuse to compensate for this loss of revenue, even though the federal states have provided them with the funds from § 45 a PBefG. The public transport authorities have mostly received these funds without earmarking them and thus do not feel obliged to pass them on. This means that these funds are not used to compensate for the shortfall in income from fares, but are used to expand services, with the result that self-supported services have to be discontinued. The public transport authorities receive the money for the compensation of the discounted tickets from their federal states and additionally demand this discount from the operating companies. In this way, they receive funds in two respects, which are, however, withdrawn from the market.

Under 2.5.8. the Commission formulates: “Article 1(1) and Article 6(1) obligation to compensate public service operators ‘adequately’.”

Point 7 of the Annex to the Regulation states that “the procedure for granting compensation must provide an incentive to maintain or develop […] the provision of passenger transport services of a sufficiently high quality”. This principle is also enshrined in Article 2a(2)(b), according to which compensation for net financial effects of public service obligations must ensure the financial sustainability of the provision of public passenger transport services in the long term. This means that the compensation provided by competent authorities should enable operators to provide high quality services on a financially sustainable basis. Underfunding would lead to a deterioration of service quality. In the case of competitively awarded contracts, excessively low compensation would discourage potential bidders from participating in the tendering procedures.” The bdo therefore welcomes this clarification, which is fully in line with the intention of Regulation (EC) No 1370/2007. The clarification makes it clear that the existing practice of § 45 a PBefG of withdrawing funds from companies without at the same time lifting the rebate obligation is not EU-compliant.

2.2.3 State intervention through the imposition of public service obligations only in cases of proven market failure.

The Federal Republic of Germany complies with the spirit and purpose of Regulation (EC) No 1370/2007 with the “two-tier principle” enshrined in the PBefG of own-account transport provision on the first tier and public service transport provision in the event of market failure on the second tier. The two-tier nature of the PBefG also complies with the principle of the social market economy existing in Germany and is based on the constitutionally guaranteed right of freedom of trade.

As described above, however, the “two-stage principle” laid down in the PBefG with its rule-exception relationship of self-sufficiency (market as rule on the first stage) and public service (state intervention as exception on the second stage) is unfortunately reversed in public transport practice by the almost comprehensive public service contracting (the figure below shows the figures from 2018. However, it can be assumed that by 2021 the number of public service contracts will have increased at the expense of own-account transport).

This also applies to the public service contract via the so-called tender competition, which has increasingly displaced the medium-sized business-friendly and subsidy-free licensing competition.

The last few years in Germany have shown that classic tender competition is not well suited to ensure fair competition in the existing complex public transport structures. In many cases, it is used locally to obtain the cheapest service. This often results in a ruinous tendering process at the expense of the driving personnel. Insolvencies due to cheap offers are also a frequent consequence. The most essential core competences necessary for a functioning competition, such as the integration of local knowledge but also innovative and new business ideas, which are the basis of the free market system, are taken away from the companies and attempted to be shifted to planning offices and government agencies. Fixed tender annual cycles of 10 years prevent any innovation in the meantime. The business activities of the companies are limited to being able to offer the services as cheaply as possible with the lowest possible personnel costs, since all other bid price components are almost identical due to the tender specifications.

For the necessary innovative and digital development of the public transport market, however, more entrepreneurial responsibility and less state intervention is needed. As the EU Commission rightly proposes, a larger part of the transport services should be returned to the market on an own-account basis. The services that are required in addition and cannot be provided on an economic basis would then be left to a public service contract. This way, more ideas and innovations will enter the public transport market; better transport will be created with less tax money. Nobody in the country should have an interest in as many unused bus lines as possible. The available resources should be used in such a way that as many passengers as possible use them and as much traffic as possible is served satisfactorily with them. To achieve this, the Federal Republic of Germany needs the full commitment of the many medium-sized and owner-operated bus companies. The key to better involvement of the bus middle class is general regulations. The competent authorities must be prevented from imposing public service obligations without a needs test and without paying compensation for this through a general rule. As shown above, this unfortunately happens every day in Germany. The bdo therefore expressly welcomes the Commission’s clarification under 2.2.3 in order to counteract this undesirable development in Germany as well and thus to permit self-sufficiency and innovation.

Under 2.2.3, the first paragraph states: “However, the power of the Member State to define a service of general economic interest is not unlimited and may not be exercised arbitrarily and for the sole purpose of allowing a particular sector to circumvent the application of the competition rules”.

This clarification should be accepted in Germany, because even if public transport is a service of general interest, it is not the task of the state to provide it itself.

It is not expedient that local public transport in Germany is no longer planned by the companies themselves, but by consulting companies bought in by the responsible authorities, thus securing their raison d’être and permanent employment through increasingly complex awards. It is irrelevant whether own municipal companies organise the transports (direct awards), or whether the assumption of all entrepreneurial and economic responsibility is transferred to the public transport authorities and special-purpose associations through competitive tenders. Today, there is hardly any transport left for the real self-economy market; the often only market-economy share is the tendering of pure transport services. Transport is withdrawn from the market, although it is clear to all parties involved that the essential innovations and costs arise on the supply side, which in these cases is nationalised.

It goes on to say: “According to Article 2(e) of Regulation (EC) No 1370/2007, a public service obligation is a requirement with a view to ensuring public passenger transport services of general interest which the operator, having regard to its own economic interest, would not have accepted or would not have accepted to the same extent or under the same conditions without compensation”.

It is about ensuring passenger transport services and not about municipalising them. It is explicitly called “transport services” and not “driving services”.

In addition, it is clarified that “the Commission considers that it would not be appropriate to link certain public service obligations to a service which is or can be satisfactorily provided by undertakings acting in accordance with market rules under normal market conditions which are consistent with the public interest as defined by the State, for example in terms of price, objective quality characteristics, continuity and access to the service”.

The approach chosen by the consultancies and often pursued by the public transport authorities to prevent private-sector transport by imposing additional requirements is rightly regarded by the Commission as incompatible with the internal market. This insight should also be used in Germany to clarify the PBefG so that the last market-oriented, self-supported services are not forced into state tendering or direct award and thus deprived of innovative incentives.

The draft states that “there can only be a need for public services if there is user demand and this demand cannot be satisfied by the free play of market forces alone. In order to meet the need thus identified, the competent authority should give preference to the approach which least restricts essential freedoms and least disturbs the proper functioning of the internal market.”

The bdo welcomes this clarification, because it corresponds to the basic idea of the social market economy and freedom of trade. First of all, all market participants should be allowed to cover existing needs. This will always be the case if there is real user demand; in other words, if users want to accept an existing offer and are also willing to pay a reasonable fare for it. If there is to be an additional offer, then this can be covered and financed by a public service contract. As a rule, these services are politically desired and not market-oriented, and must therefore also be financed from taxpayers’ money. The separation of the transport services to be provided by the market from the politically desired additional transport services thus leads to the urgently needed transparency. For in this way it can and will become permanently visible whether the additional politically desired and financed services are also accepted by the passengers. As a result, it becomes clear with which effort which effect is achieved, so that after an appropriate period of time the meaningfulness of additional public services is automatically questioned. Unfortunately, up to now there has been no procedure according to which this necessary transparency is carried out. It is precisely the consulting firms that have been commissioned that have no interest in disclosing misjudgements.

It goes on to say that “the Commission considers, however, that the inclusion of cost-covering services in the scope of public service obligations should normally be justified by the objective of ensuring a coherent transport system, in particular at geographical level, and of reaping the benefits of positive network effects, rather than limiting the level of compensation”.

This is a very important clarification. The bdo welcomes this statement, with which the Commission rightly makes it clear that bundling of regular services, which can be provided and financed by the market economy, with other politically desired unprofitable lines may not be misused to finance politically desired services or even to break up private structures. The procedure of line bundling, which is now common in Germany, must therefore no longer be abused to undermine the market economy through politically motivated transport. Unfortunately, this type of line bundling is often found in practice where own-economy transports are deliberately to be displaced. In these cases of abusive line bundling, the companies have hardly had a chance to take action against this. They are thus forced out of the market. The Commission has recognised this and rightly intends to take countermeasures.

2.2.2 Prefer the general rule as a milder means

Under 2.2.2, the Commission states that the general rule is to be preferred as a milder means of market intervention by the competent authority, as it is open to all market participants and can thus be carried out in a transparent and non-discriminatory manner.

Unfortunately, however, the opposite practice is widespread in Germany. Transport services tend to be pushed into public service instead of choosing the less intrusive means of general regulation. This practice has been deplored by the bdo for years. It is neither covered by the PBefG nor by Regulation (EC) No. 1370/2007. The following clarification is therefore required under 2.2.3: “Before awarding service contracts, the competent authority must check whether the objective cannot also be achieved by a general provision.”

The Commission correctly states that not every compensation payment is permissible in the form of a service contract or an in-house award. In the opinion of the bdo, the clarification of possible clawbacks should be formulated more clearly, as it is ultimately a matter of tax-financed public funds of the citizens that should not be spent indefinitely and uncontrolled or even without reason.

Unfortunately, Germany fails to realise that recital 5 states that “many” passenger land transport services that are necessary in the general economic interest cannot currently be operated commercially. This means that the European legislator does not mean “all” and also not “most”, but only “many”. In Germany, only a few own-account transport services remain, as the previously described misguided development supported by strong consultancies in Germany makes the rule intended by the EU the exception.

The Commission’s draft guidelines also display a necessary foresight, as they take current developments into account. It recognises that important requirements for social conditions as well as for environmental protection can best be implemented if these requirements - as is common in Germany - are deposited via local transport plans and then implemented as far as possible through the diverse ideas of the market participants. The Commission makes it clear that general regulations can intervene in market behaviour at any time. Irrespective of approval periods or contracts, the competent authorities can use general regulations to influence transport at any time and also implement political requirements. In return, these must of course also be financed. The costs required for this are usually much lower than complicated awards of public service transport contracts. The general provision also allows for regular fine-tuning, e.g. to update political or also traffic requirements. In addition, there is constant cost transparency due to the ex post control.

The Commission also makes it clear that a basic service should be provided as commercially as possible under social aspects and only the necessary supplements that the free market cannot provide should be financed within the framework of general regulations. Only in exceptional cases will further state awards be necessary.

Get transparency and cost overview

In summary, it can be said that the Commission has recognised undesirable developments in Europe with this draft guideline and therefore wants to take sensible and sustainable action. In principle, this is very welcome. However, the Commission should work with concrete examples of how, for example, a necessary needs analysis can be carried out within the framework of local transport plan design. Concrete specifications should be made in this regard, which could then also find their way into the PBefG. Here the Commission remains too vague. The practice in the field of local transport plan design shows that it is often rather a matter of political wishful thinking without taking into account the actual financial possibilities. Needs analyses are only carried out in the rarest of cases. This should be effectively countered.

For services that cannot be operated under normal market conditions, we suggest that they be subject to a regular review so that budget funds are not wasted. It is often emphasised that additional transport services must be created, especially in rural areas. This approach is understandable and is very much welcomed by the bdo. Innovative on-demand and pooling services can be a suitable means of providing a good public transport service, especially in rural regions. In recent years, there have been various and numerous projects funded by the federal and state governments. There is no overview of costs and benefits. In our view, many on-demand services have been integrated without reason into the public service contracts of municipal companies at the expense of the taxpayer and thus withdrawn from the market. Transparency is necessary here if one wants to get an overview of the meaningfulness of these services. Therefore, a regular review of the use and costs per transport case should be carried out in order to avoid false incentives. In order to achieve this, a compulsory register should be set up at federal level, in which all transport authorities enter their transport services requiring subsidies. This is particularly important with regard to transport services that are operated for smaller user groups and thus have a higher subsidy requirement per user and use. For reasons of transparency, such a register should also contain which consultancy firm was involved for the public transport authorities, which user forecast is assumed and which costs per user are forecast. This would make it possible to compare the different approaches and prevent unsuccessful concepts from continuing to be sold on the “consultant market”. In addition, the local political bodies would be able to regularly assess the success of their decision. It would be easier for all public transport authorities to implement successful models without the political interest in public transport being extinguished by failures.

The creation of this necessary transparency is also important with regard to the Green Deal and the achievement of climate targets. Thus, the benefits and costs of alternative drives should always be determined here as well. Not every expensive expenditure in e.g. hydrogen technology is always best suited to achieve the climate goals with the available financial possibilities. When drawing up the local transport plan, it must therefore be examined locally in each individual case which technical type of drive is the most suitable. On the ground, political wishes and actually sensible measures, such as the use of e-fuels, can diverge. Objective and verifiable parameters must therefore be set that prevent ineffective spending; after all, we will not achieve the climate targets in Germany on doubling passenger numbers if we are not even able to maintain existing services due to a lack of spending controls.

Bundesverband Deutscher Omnibusunternehmen e.V.

Source of the chart: bdo ÖPNV Transparency Register